How memoir photography is changing

In our modern world, we are surrounded by images. In fact, we are almost obsessed with images. Furthermore, smartphones allow everyone to snap photos in an instant and immediately share them with friends, family or even the world at large through the medium of social media.

Anyone born in the twenty-first century will grow up with a detailed record of their childhood as doting parents capture each precious moment, each smile, each milestone, with every image available for viewing instantaneously.

When they come to creating their own LifeBook autobiographies in decades to come, what a wealth of photos will the Zoomers have collected over their lives – and what a huge job it will be for them when it comes to selecting those that make the final cut.

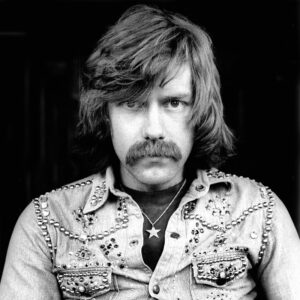

Photo courtesy of Nigel Gray, Memoir Author and Photographer

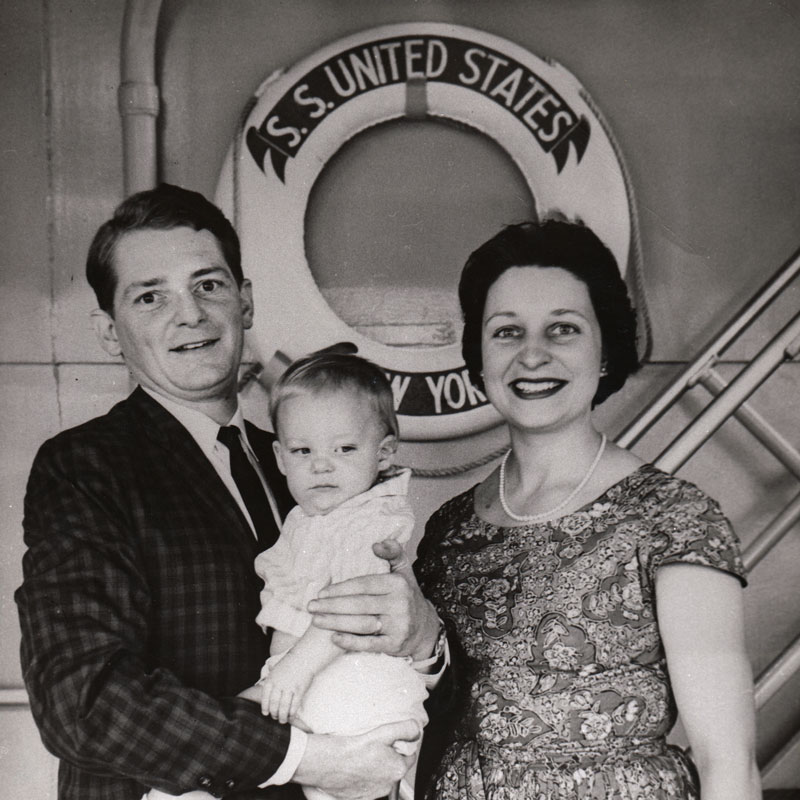

For many of our LifeBook authors, however, the choice is somewhat more limited – although, nevertheless, choosing which images to include and which to leave out is often not an easy task,. Instead of trawling through thousands of digital images on the computer, it is the photograph album that our authors turn to. Within those pages are hard copies of photos featuring family members, people met, places visited, events attended, much-loved pets and other important LifeBook vignettes, quite literally snapshot moments of lives well lived that have been kept for posterity.

In the days when a traditional camera using film was the only method of photography, unless the photographer was a keen hobbyist, far fewer photos were taken. Films cost money to buy and then there was also the developing to be paid for, meaning there was considerable expenditure involved. The knock-on effect of this was that photo-taking tended to be limited to special occasions, such as holidays, outings, weddings and visits by or to friends and relatives, unless the photographer, eager to have the images developed, were to take a few random snaps to ‘use up the film’.

Furthermore, photography could be a precarious pastime. For example, the film had to be treated with care, especially when loading and unloading. Light getting into the camera could destroy everything, moisture too was disastrous and even excessive heat could mean ruined photos. These days, the Cloud allows for any number of images to be safely stored without risk of damage or loss, and even those that have been deleted can be retrieved if the photographer has a subsequent change of heart.

One difference that is immediately noticeable when comparing modern amateur images with those from the past 60 or 70 years is the quality of the photography itself. With a maximum of 36 photos to a film – and most offering either 12 or 24, often in black and white as opposed to colour – each frame was precious. Careful thought was given before pressing the camera shutter – is this something worth recording? – and usually only one photo would be taken of each potential subject. Contrast that with today when a person could easily click their phone camera hundreds of times in a single day, with every possible photographic opportunity chronicled.

When using film, with only one chance per image and often a long wait (sometimes weeks, even months) before any photos might be viewed, it is hardly surprising that the resulting images often left something to be desired – too much sky or foreground, heads chopped off, messy backgrounds, bad light and poor composition to mention just a few of the most common faults. In contrast, today, with modern cameras and phones, pictures can be instantly checked and if found lacking in any respect, replacement shots can be taken immediately.

Alternatively, having recorded numerous versions of the same subject, the best photos can be selected for keeping and the rest discarded. Because of this ability to self-edit, photographic technique can improve rapidly, added to which are the numerous possibilities to instantly alter and enhance photos at will or to create some dramatic special effect. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that many digital photographers can produce impressive results.

For inclusion in a LifeBook, print copies of photos must first be scanned to convert them to digital images. Once this is done, the magic can happen. For example, tears can be ‘repaired’, colours sharpened and balanced, ‘red eye’ eliminated, backgrounds (or even people) removed and incorrect exposure or colour imbalance improved upon (what cannot be resolved is an out-of-focus shot). Whatever the problem, digitalisation can more often than not come to the rescue.

All this is, of course, very laudable and yet there is a strange charm to be found in an imperfect print that is showing signs of its age or era. These pictures are of another time when the pace of life was a little slower and waiting for the developed prints to return from the chemist offered an exciting anticipation that formed part of the whole photographic experience.

As a result, the images you see in a LifeBook might often seem unsophisticated and amateurish but that does not mean they are not precious or of interest; quite the opposite, in fact. They are irreplaceable fragments of a personal history, each telling its own unique story and each containing a special memory that, through the LifeBook pages, can be preserved and shared for ever.

By Halima Crabtree, LifeBook Editor

If you are interested in penning your story, please get in touch. You can also find memoir and autobiography testimonials here.