Extract from “Putting the soul back into business” by Dr Tamara Howard

Another man who built a company, made money and then, ‘retired’ only to start a social business is Roy Moëd. Roy is a classic entrepreneur, so it’s no surprise he couldn’t manage to retire quietly, but his motivation to start a social business came later in life. In his early career he was too busy working to think about much else. Book by Dr Tamara Howard.

Roy’s Story – helping the elderly

Roy began his story by explaining that his academic performance had been weak. A series of family moves at just the wrong ages left him at a disadvantage in his studies. He moved from South Africa to Jersey when he was seven years old and, he explains, “At the time, the school system in South Africa was well behind that of Jersey.” Seven is an important age in education and Roy struggled to catch up. He was ‘kept down’ one year and regularly received a caning from the headmaster. “Every year, I was worst in the class.” The family moved to London in 1967, and Roy, now a young teen, found himself enrolled in the local grammar school and, once again, behind the rest of his class because the English schools were far ahead of those in Jersey.

In 1969, the grammar school was converted to a comprehensive and Roy’s father, concerned about his youngest son’s education, enrolled him in a private school. But it was the same old story. All the classes were ‘out of synch’ with those in Roy’s previous school and Roy struggled. He studied for A-levels in French (which he spoke fluently), Economics and Maths. However, Roy didn’t do well in his exams, so he didn’t go to university. As a next step, Roy enrolled on a catering course at Westminster College and during the summer, took a job running the first drive-in restaurant in Jersey, which was owned by his father.

This role was a ‘baptism of fire.’ On the second day, the chef walked out because he didn’t want to be bossed around by the young, inexperienced son of the owner. In spite of this and other challenges, Roy persevered throughout the summer and learned a lot – the hard way. One thing he definitely learned was that he did not want to be in the catering business so when the autumn came around, he set out to find a job in London instead of taking his place at college.

Soon, Roy found what would be the first of 29 different jobs, all in rapid succession. “I was very, very good at the interviews,” explains Roy, “but the day to day jobs just didn’t work out for a variety of reasons.” One position of note was at a restaurant, Lyons Corner House. Roy noticed two jobs advertised, one of which was a much better paid supervisor’s role, requiring the skill of ‘smoked salmon slicing’. When Roy sat waiting for his interview he spoke to a fellow applicant and asked him which job he wanted. The other candidate replied that he was after the lower paid, less skilled role. On that day, both of these applicants were successful and Roy became a smoked salmon carver as well as a supervisor. At the same time, he learned a great lesson “If you don’t ask… you don’t get.” Of course, Roy had to go home and learn how to slice smoked salmon, but he got the job!

More jobs followed in swift succession. One position of note was as Night Manager at GAD (Great American Disaster), a famous London nightclub. In the line of duty, Roy had to fire a ‘shady employee’ who had been pilfering and appeared to be involved in illegal activities. Four days later, Roy himself was fired without explanation. Even now he is unsure what he inadvertently stumbled upon that day. There was no malice on the part of GAD because every time Roy went back to ask them for a reference, they gave him an outstanding one. Roy wonders if, perhaps, he had seen something that the bosses didn’t want to explain.

Roy’s other jobs included running a hotel, working in a kibbutz in Israel and a variety of sales positions. The final job that catapulted Roy into his entrepreneurial career was as a commissioned salesman, making most of his salary by selling non-dairy cream for a firm of butchers. Roy explains what happened. “They thought I would go around and sell a container here and a container there, going from shop to shop. Instead, I went to companies like British Airways and sold hundreds of times the amount that was forecast.”

The entrepreneur emerges

While selling to British Airways and similar businesses involved with airline catering, Roy uncovered the need to supply pineapple juice in small quantities to the caterers who supplied Iran Air. The quantities were too small to be of interest to the existing suppliers. Roy mentioned this situation to a friend and together they decided to try to solve it. Roy would supply the money (he was still working as a non-dairy cream salesman) and his friend supplied the labour, and they made a deal to supply pineapple juice for Iran Air and mineral water for Japan Air. The deal was that Roy would get 50% of the business for his investment.

Together they bought a yoghurt machine and a tea urn, and rented an inexpensive room in a cheap part of London. They bought tins of pineapple and bottled mineral water and every day they made six cases of pineapple juice plus mineral water, in small, airline portions. Gradually, the quantity increased to ten cases per day. The deal was that if this small business successfully filled the orders, they would be given the much larger order for orange juice. Things went well. Roy’s partner did the work while Roy supplied the funds, did the books and kept on working his day job. Then, disaster struck.

As a result of this over-performance in selling so much to airline suppliers, the CEO became jealous and Roy’s manager was ordered to fire him. However, his manager felt so bad about the way that Roy had been treated that he went out of his way to create opportunities for Roy to find more work and grow his new business. At this point, Roy threw himself into getting sales for his growing airline supply business, which they named Pourshins.

In the first year, 1978, Pourshins achieved a turnover of £30,000. When Roy got further involved as the company driver, he began to discover additional customer needs and started supplying more and more products to airline catering services. The business began to grow at a tremendous rate. Every year for the next few years Pourshins doubled or tripled its annual turnover. At the peak of its performance, it had four factories in three countries and more than 600 staff. And all of this growth was achieved organically. There were no external investors.

“It grew,” recalls Roy, “because I listened to my customers and tried to solve their problems. I like solving problems. I’m good at it.” And solve problems he did. Their motto was ‘it never hurts to ask’. However, Roy’s business partner began to suffer from nervous ailments and after three years in the business, he sold out his share in Pourshins to Roy.

In the 1980s and early 1990s there was no supply chain for ‘chilled’ food, so Roy created one. He started a US division and began to manage the airline food supply chain for most of the US carriers. But Roy noticed that he was forever trying to recover from the annual crises that depressed the airline business. Roy called them ‘the seven plagues’ and they included the avian flu scare, the 9/11 attacks and the global economic downturn – all events that had a dramatic effect on air travel. In addition, the airline catering business became increasingly complex and bureaucratic as governments introduced more stringent regulations. So Roy took a careful look at Pourshins to see how he could restructure with the aim of minimising risk.

Roy began to consider outsourcing different operational areas. He also started to sell off non-critical components in order to reduce his exposure to market fluctuations. Finally, he decided to get out of manufacturing altogether, selling some of his companies and keeping only the distribution component. As a result of these changes, his staff numbers dropped from 600 to 140 people. Many of the staff transferred with the businesses, but some did not. When redundancies were necessary Roy was always honest and straightforward and kept everyone informed about what was happening and why the reorganisation was essential.

He kept the US operation and a large warehouse at Heathrow for his distribution business until, having spoken to a customer about coordinating the delivery of knives and forks along with the food, Roy discovered another opportunity and reshaped his business yet again. With the growth of computer technology outsourced logistics, known as 4PL (Fourth Party Logistics) and communications, he realised that his real skill and opportunity was in managing customers’ supply chain needs in a timely and cost effective manner. He didn’t need to make the products, nor did he even need to supply the warehouses and trucks to distribute them, so he reorganised and sold these businesses while continuing to distribute the products from them.

When Roy outsourced his warehouse and his distribution services, he reduced the headcount again, from 140 to 60 staff. Pourshins would now act in a sales and supply chain management capacity, sourcing the customers’ needs from the best supplier at the time. This approach cushioned his own business against the wild fluctuations in the airline industry. He threw a party for the 80 staff who were made redundant. “I didn’t feel I had to hide the fact that they were going,” he explains. “It wasn’t their fault. I wanted to treat them well.” Most soon found jobs in the same industry and carried on working with Roy and his team, and the ones that stayed behind realised and appreciated the kind of company in which they were working.

Within the new structure, Roy continued to deploy technology in new and interesting ways to advance his business. By this time, the business had a turnover of $100m and employed only 32 people. Over 30 years, Roy had reshaped his business four times, always having just enough vision to keep ahead of the rapidly changing business environment.

What next?

In 2007 Roy finally sold the company because, he says, “I wanted a change. After 33 years of solving problems and driving the business alone, I was tired. My father had always said that if you want a business then find one without staff and without stock, like insurance or estate agency, where one call could be for £100 or £1m. At its peak, Pourshins had 600 staff and £2m of stock.” Roy took what he described as a “gap year” and others would call a holiday. He and his family spent six weeks in South America doing things like flying over the lakes in Chile in a small plane. He then bought a polo farm and set up a club near Windsor.

Despite enjoying his leisure, Roy couldn’t help himself and started another business. This business, called Meet Me, focused on airports – Roy’s old stomping ground. Meet Me was to be a computerised system to link up travellers with the drivers who had been sent to collect them, replacing the old-fashioned system of a sign with the passenger’s name on it. After almost two years in development, and having been installed in Heathrow’s Terminals 1, 2, 3 and 4, the business details couldn’t be worked out satisfactorily with the airport, so Roy went back to playing polo and retirement.

Meanwhile, outside his business life, Roy started to work with the homeless and in 2004 he and his wife were approached to help out with Crisis At Christmas, a charity that supplies food and other necessities to homeless people during the Christmas celebrations. Roy was already aware of this organisation because airlines provided some of the food. He went along thinking that he could be a driver and have no responsibility, but within two days found himself in charge of managing a shift in the logistics department. He supervised more than 300 drivers (all volunteers) and 100 vehicles, organising the pick-up and delivery of food, medical supplies, equipment, people and whatever else was needed over a ten day period. From that point on, Roy and his wife took part in this effort every year.

Roy became deeply interested in the issues around homelessness and the reasons behind it. “Many were depressed,” he explains, “and I began to wonder: how do you make people care about themselves when they are depressed? How to you get them to engage with life?”

Roy’s ‘ah ha’ moment

These thoughts whirled around in Roy’s head and he began to think about his father – now old, blind and feeling he had little to live for. His father was depressed, and Roy wondered how he could motivate and help him. He decided to get his father to tell his own life story – that of a Dutch-born Jew in South Africa who moved to Jersey and then London, setting up businesses and raising a family of four children along the way. The regular weekly storytelling sessions gave Roy’s father something to look forward to and when they came to an end, his father had a book of his family stories, all preserved in one place. The process helped his father and it helped Roy – it was a ‘win/win’ solution.

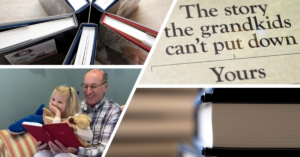

Roy thought about the process. He knew that there were many other older people just like his father – perhaps depressed and housebound – with nothing much to look forward to each day. Roy also knew that there were other families like his, who would appreciate the treasure of a family history and capturing memories and moments that would otherwise be lost. This activity could be an opportunity to make a lasting difference and, always the entrepreneur, Roy wondered if there was a way to roll out his idea, to make it a self-sustaining business that could reach more and more older people and help more and more families around the world.

Roy can’t help it – he solves problems and thinks ‘big’ and now his vision became to “move the needle in the way in which elderly adults enjoyed their lives.”

In 2010, while advising a friend’s daughter, Alise, on social entrepreneurship, he asked for her help in researching his concept as a social business. They tested their ideas on relatives and friends and started the business in a barn at Roy’s home. Roy could now enjoy the challenge of applying his entrepreneurial skills to solving a very real social problem.

Together, he and Alise came up with a sustainable format by deconstructing the process. The business could use interviewers who were local to the ‘author’ and could regularly visit the older person. The interviews would be recorded and uploaded, and then downloaded by a ghost-writer who would turn them into a book which would then be prepared for typesetting and printing by an editor. In this way, geography wasn’t a restriction and the business could reach around the world. LifeBook was born and was truly scalable.

“I could have just carried on just doing Crisis at Christmas,” Roy says, “but I wanted to create something that would make a difference. With LifeBook I have created something that can, one day, be independent of me and can impact the lives of hundreds or thousands of elderly people and their families each year. For me, that’s hugely exciting and rewarding. I feel like I have made a tiny difference on this earth.” As Roy’s story shows, for the majority of his working life, all he thought about was the business. He wasn’t a bad boss or employer, but his business aim was to make money and he threw himself into this work with an all-consuming passion. It wasn’t until he neared retirement that he had the perspective to consider other motivations. Being first and foremost a business person, it didn’t occur to him to set up LifeBook as a charity, so the social enterprise model was a perfect way for him to deliver social benefit.

Roy with his copy of “Putting the soul back into business”